Three Somali Children were placed in foster care when their mother was murdered. The children’s aunt wanted them to come and live with her and her family, but the child welfare agency was concerned because they were already a large family living in a three bedroom apartment. In addition, the aunt had recently been diagnosed with cancer. They decided to hold a Family Group Conference to develop a permanency plan for the children. Together the family representative and a coordinator arranged logistics. The meeting was held in the Community Room at their apartment building on a Saturday afternoon and the grandmother prepared all the food for the conference. More than 40 family members and community supports attended the meeting along with the social worker, guardian ad litem, two community resource workers, two facilitators, and an interpreter. The family opened the conference with an elder reading from the Koran. After the service providers shared relevant information, the family met in private for an hour and a half to discuss their options. Afterward, they shared their plan for the children – for them to live with their aunt and uncle. The plan addressed how the extended family would support the aunt and uncle with housing, schooling, child care, transportation, breaks from parenting, and a back-up plan. Service providers asked a few questions to strengthen the family plan and by the end of the conference they were in support of the children moving to the aunt and uncle’s home permanently. The conference closed with an aunt reading a letter the grandmother had written the night before about the importance of bringing the children back to their family and community, where they belong. -Case example from this month’s featured promising practice, Family Involvement in Child Welfare Practice

Cultural competence, strengths-based practice, and understanding and working with a child within the larger family and community context are regarded as important principles in child welfare practice today. Implementing these principles, including having the knowledge and tools on hand to do so, had, of course proved far more challenging for most child welfare practitioners. This is particularly true for those working with refugee and immigrant families who become involved with the public child welfare system. Newcomer family and community structures are more likely to be unfamiliar to child welfare staff, their strengths not as easily recognized, and some may even be misunderstood as liabilities. In this Fall 2007 Spotlight, BRYCS highlights the culturally competent approach of a national agency. Migration and Refugee Services of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (MRS/USCCB), specializing in child welfare services to refugees and immigrants for over 30 years, in addition to featuring models being implemented, tested, and disseminated by two major child welfare entities. The American Humane Association (AHA) and The Annie E. Casey to an emphasis on working together with family and community structures as strengths and resources. Most importantly, they offer practical tools and resources for practitioners to use when serving refugee and immigrant families who enter the public child welfare system.

Using Family and Community Centered Child Welfare Practice with Refugees and Immigrants

Family and community centered child welfare practices are particularly applicable to refugee and immigrant families for several reasons. Though refugees come from a variety of countries and cultures, most come from collectivist societies with values that are similar to those followed by family and community centered child welfare models. For example, collectivist cultures are group-oriented, highly value extended interpersonal relationships with family and community members, and may particularly honor and respect the opinions and advice of elders, including religious and community leaders. In family and community centered child welfare models, these cultural values are recognized and worked with by focusing on and utilizing the family’s strengths, rather than automatically perceiving cultural differences as deficits.

In addition, other components of families’ cultures are viewed as strengths with this type of practice. Families are encouraged to develop plans and solutions that work for them, which often involve their own natural support systems and communities. Mainstream service providers are often unaware that many of the refugee and immigrant communities around the United States are well organized and engaged in providing support to families every day, both at the local and national levels. With these family and community centered child welfare practices, refugee and immigrant families’ existing resources are clearly identified and incorporated into their child welfare service plan.

Moreover, family and community centered child welfare practices are beneficial for refugee and immigrant families because they give a voice to populations that frequently feel powerless, particularly with regard to the child welfare system. Many refugees and immigrants are members of groups that have experienced discrimination, including persecution in home countries and discrimination in the United States. Whether due to prejudice or barriers such as language, it has been all too common for child welfare workers to make decisions for refugee and immigrant families, rather than with them. These models of family and community centered child welfare practice provide a needed structure for collaborative decisions that are more likely to be based on family and community strengths, draw from a wide range of resources, and provide permanency and well-being for children in the long run.

Overview of Family and Community Centered Models

Migration and Refugee Services (MRS/USCCB)

The importance of understanding and working with indigenous family and community structures when serving refugee and immigrant children has been recognized by refugee resettlement agencies throughout their decades of specialized services to these families. Migrations and Refugee Services of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (MRS/USCCB) and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS), in particular, have provided family reunification services to the most vulnerable of these families and culturally competent foster care to unaccompanied refugee children for 30 years. MRS/USCCB currently allocates significant resources to supporting the safety, permanency, and well-being of the most vulnerable of these children and families. At this national office, professional social workers are organized into family reunification and foster care teams that work closely with the more than 200 local agencies that make up the MRS national refugee resettlement and foster care network. MRS staff assist local agency staff by walking them through the challenging situations that frequently arise when resettling refugee families, bringing additional resources to bear and ensuring support for fragile families (for example, those who are caring for others’ children or children who have just reunited with their families after years of separation). Currently, over 500 vulnerable children (including refugee/asylee, Cuban-Haitian, and unaccompanied undocumented children in federal custody) are assisted by MRS national staff each year.

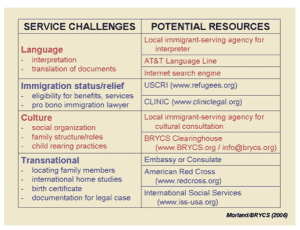

To serve these families, MRS staff continually learn about and work together with indigenous family and community structures. Looking beyond the nuclear family, MRS staff view the child within a complex social ecological framework. For example, staff may engage clan leaders or elders to work together with extended family members to develop the best opportunities for a child’s protection and nurture. In addition, they work together with partners such as the American Red Cross to locate family members in other countries and consular offices to provide needed background information and paperwork, such as birth certificates. Organizations such as International Social Services can assist with home studies or develop local support services to aid in family reunification in a different country, if this is in the best interest of the child. (See Diagram 1)

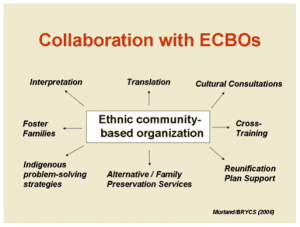

MRS staff are also accustomed to working together with a range of community organizations that can provide additional resources for child and family. These include mainstream institutions, such as the child’s school, as well as ethnic community based organizations (ECBOs) and religious institutions that include community leaders and a natural web of helping relationships. These ethnic communities can provide additional benefits, such as assisting the child in developing a positive ethnic identity or maintaining language and culture by helping locate kinship care or culturally appropriate foster homes until the child can return home. These organizations can also help to bridge the family with child welfare requirements by providing interpretation and culturally competent services, such as parenting support groups. (See Diagram 2)

Diagram 1

Diagram 2More recently, public child welfare agencies have begun to use family and community centered models. These models may go by different names but share underlying values such as: all families and communities have strengths, families can make well-informed decisions about keeping their children safe, and that child welfare outcomes will improve when families are involved in the decision-making process. In the two models discussed below, the overall key component is the “family meeting”, where extended families and community supports design the plan for the safety and well-being of their child.

Family Group Decision Making

FGDM recognizes that families have the most information about themselves and emphasizes that families have the responsibility to care for, and provide a sense of identity for, their children. Not only is FGDM a practice that is family and community centered, but it is culture-and strengths-based.[8]

Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) is one such family and community centered practice. If a child is involved with the child welfare system and this approach is used, the child’s family has a meeting to develop a plan to protect their child from further abuse or neglect. The family members- not the professionals involved- are the primary decision makers and determine what is best for their family.

This model is based on practices from New Zealand and Oregon that began in 1989. In New Zealand, the model resulted from cultural issues raised by the Maori, an indigenous group of people, who felt that some child welfare practices were alienating children from their family of origin. In addition, there were issues of institutional racism and a lack of consideration of components Maori culture including the importance of extended family and tribal affiliation.[4] In the United States, FGDM has been adopted and promoted primarily by the American Humane Association.

The Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) Process: [8]

- Referral to hold FGDM meeting:

- The referral is usually made by the social workers who investigated the case of abuse of neglect

- The referral is made to an impartial coordinator

- Preparation and planning for FGDM meeting:

- The coordinator ensures the safety of the child, first and foremost

- The coordinator asks the family “How do you define family?” and helps them decide who should attend the meeting. The offender and the child are involved as much as possible, while taking safety into consideration

- Those family members and other participants are invited. The FGDM process is described to all involved and the participants” roles are defined and communicated

- The coordinator manages unresolved family issues and informs the family that issues unrelated to protecting the child will not be discussed

- The coordinator handles all the logistics of arranging the meeting

- The actual meeting/conference:

- After the agenda and participants” roles are reviewed, the professionals involved respectfully present the facts of the case to all of the participants and they are given an opportunity to ask questions

- All professionals (and sometimes other non-family participants) leave the room and the family discusses the case in private. They must decide how to care for and protect their child from future abuse of neglect

- The professionals and other participants’ return to the meeting and the family presents and explains their plan

- Implementation of the plan:

- The plan must be written and distributed

- The professionals involved must assist the family with organizing the services they identified in their plan

- Child welfare workers work with family members to monitor the implementation of the plan

The goals of FGDM are to:

- Improve child safety

- Increase permanency (where the child lives with one family and is not repeatedly moved)

- Increase family connectedness

- Improve family functioning[1]

There are few studies that have looked at the outcomes of FGDM and most have lacked control groups.[6] However, the American Humane Association’s National Center on Family Group Decision Making has identified promising trends in outcomes for FGDM [8]:

- Decrease in the number of children living in and out-of-home care

- Increase in professional involvement with extended family

- Increase in the number of children living with kin

- Decrease in the number of court proceedings

- Increase in community invovlement

For more information on this model, see the American Humane Association’s National Center on Family Group Decision Making.

Team Decisionmaking Meetings

Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Family to Family Initiative utilizes Team Decisionmaking Meetings (TDM) as their model of family and community centered practice. Like FGDM, family members, support persons, community members, and service providers gather to develop a plan for the protection of a child. Unlike FGDM, TDMs are used every time a decision needs to be made about a child’s placement and are held for all families served by the agency using this model. With TDMs, the final decision regarding the child’s placement rests with the child welfare agency, rather than the family.

The goals of TDM are:

- To improve the agency’s decisionmaking process

- To encourage the support and “buy-in” of the family, extended family, and the community to the agency’s decisions

- To develop specific, individualized, and appropriate interventions for children and families[7]

Currently, the Annie E. Casey Foundation is in the process of a three year evaluation of its Family to Family Initiative. Each of their Family sites tracks both process and outcome data from their TDM meetings. At this point, the Annie E. Casey Foundation is in the early stages of evaluating the collected data and identifying outcomes and final outcomes will be available in a few years.[9]

For more information, see Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Family to Family Initiative as well as California’s Family to Family Web site, with a number of resources on Team Decisionmaking.

The Team Decisionmaking Meeting Process

- Introductions:

- Everyone introduces themselves

- The facilitator explains the purpose of the meeting and basic ground rules

- Family Shares Information:

- The family is invited to share information about themselves and their children

- The family is given an opportunity to ask questions about the meeting

- Caseworker Presents Case:

- The caseworker presents relevant family history

- The caseworker leads a discussion of the risk elements and safety issues

- The caseworker reviews the family’s strengths and resources

- Family’s Turn:

- The family is given an opportunity to give their perspective on the situation

- Recommended Plan of Action:

- The caseworker recommends a plan of action and invites the group to help determine if it is the best plan for the child

- Facilitator Leads Discussion:

- The facilitator leads the group in discussing the caseworker’s preliminary recommendations

- Creative solutions are encouraged

- When all possible solutions have been identified, the facilitator assesses whether a consensus has been made. If so, the agreed upon plan is stated. If not, the facilitator will ask the caseworker to make a decision on behalf of the agency

- Conclusion:

- Action steps for implementing the plan are outlined

- The facilitator writes a summary of the team’s decision and distributes a copy to all team members [7]

Catawba County Social Services (CCSS) in North Carolina has been using a model of family and community centered child welfare with the Hmong community for about 5 years. This area of the country has the third largest population of Hmong in the United States. After CCSS managers noticed that their agency’s child protection workers were experiencing difficultly in gaining the trust and cooperation of the Hmong families with whom they worked, one of the social workers of CCSS met with the Executive Director of the local Hmong organization. After a series of meetings, it was determined that there are values within the Hmong culture that are similar to FGDM values, such as the importance of family and community. North Carolina adopted a family and community centered model called “Child and Family Teams”, which is the model used by CCSS with the Hmong today. See BRYCS’ full description of this Promising Practice.

In Minnesota, Olmsted County Child and Family Services works in collaboration with Family Services Rochester to involve families in all child protection and child welfare decisions. Family Group Decision Making is used to establish forums where families, relatives, friends, and service providers are able to come together to develop plans and make decisions to ensure child safety, well-being, and permanency. This kind of collaboration allows service providers space for statutory authority while at the same time valuing the family’s knowledge, expertise and resources. This area of the country has sizable numbers of refugees and immigrants from Southeast Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. See BRYCS’ full description of this Promising Practice.

If your child welfare agency is considering using one of the described methods, including family meetings, see the below for important considerations.

Cultural Considerations When Planning Family Meetings with Refugees and Immigrants

- Establishing Trust: Sometimes refugee and immigrant families are distrustful of public systems and it will be necessary for public child welfare agencies to establish relationships with the various ethnic communities before these child welfare models can be implemented. Child welfare representatives can reach out to directors of Mutual Aid Associations and other ethnic based community organizations; give presentations at community meetings, place of worship, and schools; and advertise collaborative projects in the ethnic media, including newspapers, radio, and television.[10]

- Interpersonal Relationships: In many cultures, people often have different levels of social status based on age, wealth, achievements, or employment role, and this power differential influences family dynamics. A common characteristic of many cultures is the high status given to community elders. For these cultures, it may be important to invite key elders to the meting and/or involve them in the coordination of the meeting and process of inviting others to come.[5]

- Communication: Families from cultures where people relate to each other more as equal will likely attempt to make sure that everyone’s opinion is heard and in general, communicate directly and freely. On the other hand, families from cultures where people’s relationships are determined by status and power, will likely expect to hear more from those with authority and may use indirect communication. In addition, families from these cultures may value avoiding confrontation and maintaining harmony.[5] These cultural differences may affect communication in various ways. For example, with some families, it may seem as though the participants are speaking rapidly, loudly, or are interrupting each other. With other families, it may appear that some members are not fully participating or are not concerned about the outcome of the meeting, due to long silences or certain individuals speaking more than others.

- Illegal Traditional Practices: Situations may arise where families wish to incorporate into their plan harmful of illegal practices that are common in their culture (for example, arranging for a young child to be married or a young girl to be circumcised). Facilitators need to be prepared to steer families towards solutions that are appropriate and legal in their new context.[5]

- Ideas of Responsibility: Some cultures tend to be more individualistic, where children are socialized to be independent, while other cultures are more collectivist, or group-oriented. Where a family falls on this spectrum will greatly affect who they choose to involve in their family meeting. Some meetings may have as few as a handful of people, while others have included over 70 extended members.[5]

- Cultural/Religious Traditions: The family’s cultural traditions, and their ideas for how to incorporate those traditions into the meeting, must be taken into account. In addition, many families consider religion to be extremely important and will want the meeting to reflect this. Some families may wish to begin their meeting with a ritual or a prayer of some kind.[10]

- Background of the Coordinator: Studies conducted on family group conferencing with immigrants demonstrate that many prefer a coordinator of the same cultural background as the family. This is also helpful with regard to language. Yet, coordinators and facilitators must also recognize that some foreign-born families prefer not to be provided with services by someone from their own community, especially if it is small and they perceive a risk that information will not remain confidential.[10]

Other Consideration to Make When Planning Family Meetings with Refugees and Immigrants

- Immigration Status: In some meetings, knowing the immigration status of all family members may be important to create a permanency plan for the child. Remember that 85 percent of immigrant families with children are mixed status families (families in which at least one parent is a non-U.S. citizen and one child is a U.S. citizen), according to the Urban Institute, so that familiarity with different types of status is important. In California, it is common for immigration consultants to attend Team Decisionmaking Meetings- particularly those who are knowledgeable about Special Immigrant Juvenile Status and other forms of immigration relief for children. In addition, representatives from foreign consulates may attend the TDMs, if appropriate.[2]

- Public Benefits and Resources: Social workers and other professionals involved in family meetings need to be aware of the benefits and resources immigrant families may be eligible for. Immigration status often determines the services for which families are eligible and it is necessary for all involved to have correct information. In addition, social workers should have clear information on any consequences to accessing resources, such as being deemed a “public charge”, which can affect immigration status. [2]

- Location: The coordinator needs to work with the family to choose a neutral location where all family members feel comfortable. Places of worship and community centers are frequently used.[10]

- Interpreters: Many meetings with refugee and immigrant families will require the use of an interpreter. All agencies receiving federal funding, which includes public child welfare, are required to provide interpreters to facilitate communication according to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Evaluation

While these family and community centered child welfare models show promising results, there have not been many outcome studies to date. It is important for those implementing these practices to evaluate what they are doing to see if it is working. To continue to develop these models, randomized trials are necessary; agencies may be able to partner with a university for this level of evaluation. Before implementing a family and community centered child welfare practice-and particularly those that include family meetings- to be sure to think through:

- Which child welfare outcomes do we expect to improve?

- How will the proposed practice improve these outcomes?

- Which families are likely to benefit from this model of practice?

- How will we decide which families will participate in this practice?

- Will we include a control group to compare the outcomes between families who used this model with ones who did not? [6]

There are a number of existing resources for conducting evaluations for this type of practice. For more information, see AHA’s National Center on Family Group Decision Making’s Evaluation and Research Tools as well as Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Team Decisionmaking Indicators and Outcomes.

Please see the list of highlighted resources, which providers the most up-to-date and useful resources on this topic available.